In the coffee room at work, a young woman hissed at me. “Sei nicht fies!”

In the coffee room at work, a young woman hissed at me. “Sei nicht fies!”

Her colleague from the accounts department clarified the point. “Are you trying to offend us, or are you just misinformed?”

“You should get out more,” suggested my boss, “You’d know better.”

What earned such scorn? A simple remark, so innocent that I thought little of it.

Some colleagues were planning a visit to Pullman City, a Western theme park near Passau. My response to the news was: Well, you know what they say. Bavaria is the Texas of Germany.

A few in the coffee room had heard this expression. Others hadn’t. Those who had heard it before, declared the expression to sound old and lame. Those who had never heard it before declared it to sound old and lame, too. Nobody could quite agree what the phrase meant. But clearly, they didn’t like it.

Americans react differently. I tell American visitors that those aspects of Bavarian culture they find perplexing make much more sense if they remember that Bavaria is the Texas of Germany. And they totally get it.

“Oookaaay”, they say with the clipped precision of a New Englander, the flat tones of the Midwest, or with complex New Jersey vowels, “so you mean that larger-than-necessary Landhof near Amberg with the religious fresco on the wall is really, like, a McMansion in Fort Worth with a Tuscan fresco on the wall?”

“Precisely,” I say. And when they see the ornate rococo church of St. Georg in Amberg, they understand more completely, since it probably resembles one of the McMansion’s smaller bathrooms.

A sticky idea

Indeed, the Bavaria-is-Texas meme has been abroad in English for quite some time. Texas lawyer and lexicographer Barry Popik, in his indispensable blog The Big Apple, traces the phrase back to 1954. A Mr. C..A. Tatum, President of the Dallas Power and Light Company, spoke about Bavaria for the Texas Salesman’s Club. During his visit, he remarked that Bavarian scenery must be among the prettiest in the world. A local returned the compliment, stating “proudly” that Bavaria is, indeed, the Texas of Germany.

This may have been a simple politeness. If a visitor came from Minsk, might not his host have declared Bavaria to be the Belarus of Germany? Flattery pays, after all.

Whatever its origin, the metaphor stuck. President Lyndon Johnson, a Texan of some stature and not a little whiskey-fuelled craziness, played it up. His daughter, Linda Byrd Johnson, visited Bavaria during his presidency and spoke of the “special bond” between the two states.

This cultivated the votes of many German-Americans, whose ancestors settled east Texas between the wars of 1848 and 1871. It was these immigrants, by the way, who taught cowboys to yodel. And America never thanked them.

What makes the comparison ring true? Americans and Germans have a love-hate relationship with their most prominent states. Like all love, and all hate, it’s impossible to justify with reason. But here are a few reasons, large and small, which bubble to the surface of the cybersphere.

My state ‘tis of thee.

Most comparisons between the two states begin by pointing out that neither is particularly happy being a state. Each was once its own country, and had to give up territory to fit into a federal union. Bavarians have not forgotten the Palatinate, and Texans will not forget the eastern half of New Mexico and Colorado. In Franconia, (a.k.a. the Bavarian Panhandle) some want to take away even more territory. And Bavaria would still be big.

Sheer size defines both states. Bigness means power, authority, and even a little arrogance—Bavaria and Texas consider themselves the most important states in their respective countries.

Fellow countrymen can detect a dismissive tone from their southernmost tips. And you know what? It bothers the Texan or Bavarian not one bit. Could it be that the rest of the country’s citizens are just jealous of their size, wealth and influence? That’s the standard explanation.

The need for speed.

One of the downsides of being so big, is that it takes some time to get around the place. That’s why Texans are, to use a Texan term, leadfoots.

The marvelous Frau A., an adopted Texan who now lives in Bavaria, blogs at schnitzelbahn.com. In April, she noted an occasion to celebrate the similarities between the two states. Texas, she wrote, was about to raise its speed limit to 85 miles an hour (136 kph). This would make Texas the fastest state in the USA.

Is Bavaria the fastest state in Germany? Yes, there are patches of autobahn in most Bundesländer where speed is not controlled. But it strikes me that a disproportionate number are in Bavaria. If you drive the A8 with any regularity, you’ll notice that the radar warnings kick in just over the border with Baden-Württemburg. All Germans like to drive fast, but here in Bavaria speed limits are considered a human rights violation.

Too much religion; not enough sex.

When my partner and I performed our Lebenspartnershcaft, we expected to have a civil ceremony in the town hall. Ah, not allowed in Bavaria, we were told, because of the Freistaat’s conservative attitude to religion. We needed to get civilly unioned in a private notary’s office, away from the gaze of impressionable others. “Bavaria, you know, is the Texas of Germany”, our celebrant reminded us.

The Baptists in Texas hold the same sway as Catholics here in Bavaria, it seems.

David Vickery, an American writer who comments on matters to do with Germany, reminded us last year that both Bavaria and Texas like to censor educational materials. The example he gave was a passage in an ESL textbook which stated, quite correctly, that those Americans who believe in a literal interpretation of the bible tend to have less education. Texas insists that there be no suggestion that Creationism does not stand on equal footing with Evolution, and so does Bavaria, it seems.

Thankfully, Bavaria is ahead of Texas in many respects. For one thing, were my partner and I married today in Bavaria, we could do it in the town hall.

But in Texas, there is neither gay marriage nor a civil union; homosexual acts were decriminalized only as late as 2003. Still, one cannot sell a dildo in Texas, and indicate what it might be used for. Legally, any object shaped like a penis in Texas must be provided purely as an aid to anatomical education. And it can’t vibrate, either.

Bavarians, you think you’re conservative….

Lose a syllable here or there.

I consulted Christine, another purebread Texan who lives in Bavaria, on the subject of language. Both Texans and Bavarians talk funny, don’t they?

“It’s a matter of perspective. Everybody talks funny to someone else,” she chided. “But Bavarians and Texans do cut corners.”

“How’s that?” I asked.

She challenged me. “Think of a typical Bavarian word.”

“Um…Brez’n

“Now think of a typical Texas word.”

“That’s easy. It’s y’all.” Y’all is short for you all, and roughly translates as euch.

“What do you notice about the two words?”

I had to confess that I could find little to compare the two, until she wrote it down. It’s the apostrophe. Both Texans and Bavarians like to ditch a sound or two when they can get away with it, and the apostrophe signals that you’re supposed to think the habit is cute. Wies’n and Stuber’l, fixin’s and sure’nuff. You can smell the folky charm that floats from the punctuation.

Ultra-America. Über-Deutschland.

What do you think of when you think of America? Cowboys? Rodeos? Drive-in cinemas? Slabs of steak? Open roads filled with Mustangs and Camaros? Fast-food restaurants with waitresses on roller skates? A traffic cop on his Harley wearing mirrored Ray-Bans and chomping a short cigar as he tells you that you have one telephone call for bail?

You don’t find all that in Massachusetts. When the world thinks of America, the first images that come to mind are quintessentially Texan.

And when people abroad think of Germany; they’re really thinking of Bavaria.

It surprises visitors to (lesser) Germany that not every beer glass contains a litre…and, indeed, that it’s made of glass. Not every woman has a bustline pushed to her chin by a tight bodice. And not every fellow is wearing leather shorts. You have to go to Bavaria for that.

Folk goes formal

For a moment, let’s think about the Japanese kimono.

It started life as a humble daily garment. The rich even wore kimono as underwear. Nowadays, the kimono is far from humble. Though it’s a folk costume, it is deemed to be formal wear, suitable for the highest social occasions.

Is this not so, too, for Trachten? If you are invited to a wedding in Bavaria, you can wear Tracht and hold your head high amongst those in gowns and suits. What started out as working gear for humble farmers and hunters, has become a kit for formal celebrations.

Bavarians may be surprised to hear it, but the same goes for Texas folk costume. Attend a wedding in, say, El Paso, and you’ll see many a man with his string tie held together by a turquoise clasp. He’ll wear cowboy boots—expensive ones, of course. And he’ll dress up his jeans with a sports coat which upholsters his shoulders in a different cloth from his body. He will scoff at those who shop at Brooks Brothers, just like a hardline Bavarian scoffs at people who dress in dreary old lounge suits.

Do you deserve to be rich?

“Texas is about oil. It defines the place,” remarked one of my colleagues as we discussed the matter further. “We don’t have oil to make us rich.”

“But you do have salt,” I countered. “Or, at the very least, you had someone else’s salt passing through. It made Bavaria well-to-do, in the same way oil did for Texas.”

“Hmmm…” he thought. “Black gold versus white gold. You might have a point…”

Indeed, and the point is this. The rest of the country thinks that both Texas and Bavaria got rich through dumb luck. And somehow, neither Texas nor Bavaria earned their wealth properly. That is, not through knowledge, intelligence, sophistication or hard work. Otherwise, both states would be full of country bumpkins, and skint ones at that.

I suspect this was what my colleagues objected to the most. Bavaria has a long history of culture, refinement and education; Texas, on the other hand, is a full of…well, hicks.

Alas, this just proves my point. Texans live with the same frustration.

Yes, there was natural wealth in Texas. But like Bavarians, Texans used this natural advantage to create something richer. Houston has one of the finest opera companies in the world. Dallas boasts astonishing collections of visual art. The capital Austin, like Munich, is home to one of the largest student populations in its nation—which gives it a lively music and political scene. The climate and a lifestyle of abundance have helped attract creative and high-tech industries. Yet nobody thinks of this when they think of Texas. Just like Bavaria.

My colleagues agreed. If that’s what it means, they said, then the saying is correct. Bavaria is best known for her rustic scenery, when her thinkers, artists, scientists and businessmen really make the place cool.

This settled the argument, until I pointed out that the best known “Pullman City” in North America is actually a suburb of Chicago. Then it started all over again.

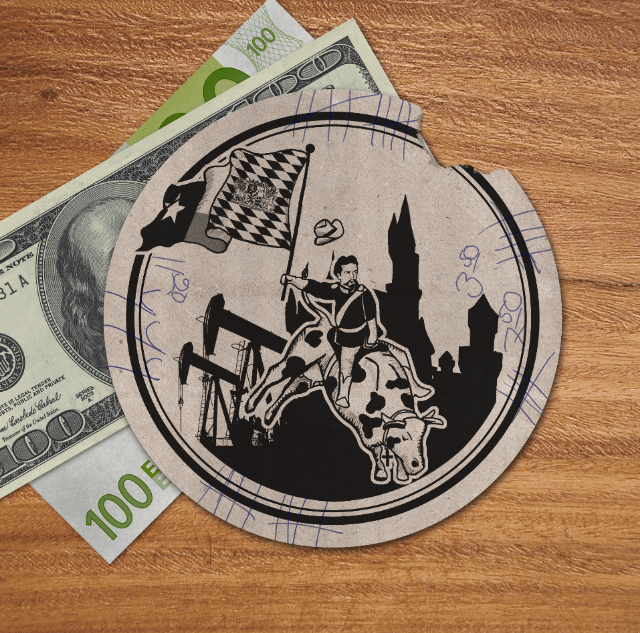

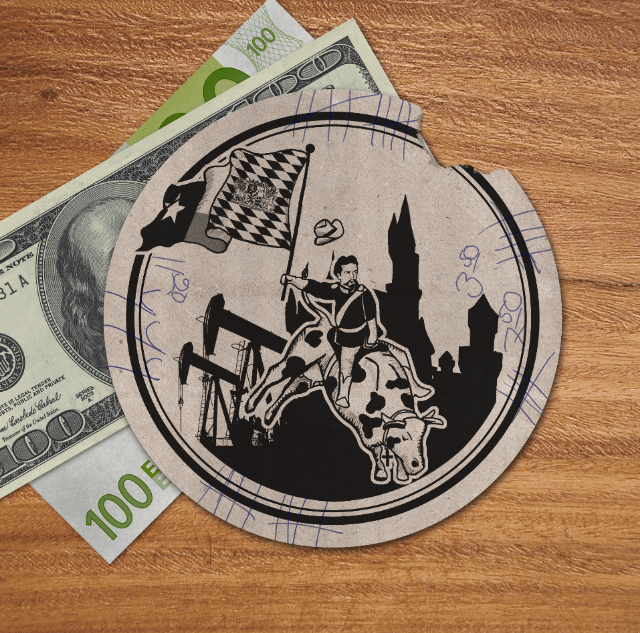

Illustration of Rodeo Ludwig by Florian Nöhbauer & Leo Slawik